The Chicago Fire - Oct 8th, 1871

No one knows how the fire started in the cowbarn at the rear of the Patrick O'Leary cottage at 137 DeKoven Street on Chicago's West Side. A long investigation and many witnesses were unable to determine anything definitive.

No one knows how the fire started in the cowbarn at the rear of the Patrick O'Leary cottage at 137 DeKoven Street on Chicago's West Side. A long investigation and many witnesses were unable to determine anything definitive.It was first noticed by a Drayman Daniel Dennis Sullivan, who just happened to be sitting on the sidewalk almost opposite the property. The O'Leary family were all in bed and asleep at the time. Theories include a stray ember from a chimney to arson of course.

The blaze began around 9 p.m. on Sunday, October 8, 1871. By midnight the fire had jumped the river's south branch and by 1:30 a.m., the business district was in flames. Shortly thereafter the fire raced northward across the main river.

The waterworks were evacuated although the tower was not badly damaged and is one of the very few original buildings still standing in the city. During Monday the fire burned as far as Fullerton Avenue. Rainfall which started about midnight helped put out the last of the flames. By the time the fire was eventually extinguished, 300 Chicagoans were dead, 90,000 homeless, and the property loss was over 18,000 buildings totaling some $200 million, about 1/3 of the city's value (and remember this was 1871!).

The city remained so hot that it took a day or two before it was possible even to begin a survey of the physical damage. According to the papers, in some instances when anxious businessmen opened their safes among the rubble of what was once their offices, precious contents that had survived the inferno suddenly burst into flame on exposure to the air.

Shortly after the fire, Stephen L. Robinson, a North Division resident whose home was not burned, set out with a printed map of the city to mark what was still standing. Among the few scattered survivors he noted were the mansion of Mahlon Ogden (brother of William) on Lafayette (now Walton) Street north of Washington Square Park, and the much more modest home north of Armitage of police officer Richard Bellinger, both of which were saved by a combination of vigilant dousings and good luck. On the South Division the Lind Block was left standing a forlorn watch over the downtown. Bizarrely, the O'Leary cottage in the West Division was also safe and sound in front of the ashes of the barn.

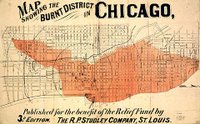

The so-called "Burnt District" encompassed an area four miles long and an average of three-quarters of a mile wide--more than two thousand acres--including over twenty-eight miles of streets, 120 miles of sidewalks, and over 2,000 lampposts, along with countless trees, shrubs, and flowering plants in "the Garden City of the West."

The so-called "Burnt District" encompassed an area four miles long and an average of three-quarters of a mile wide--more than two thousand acres--including over twenty-eight miles of streets, 120 miles of sidewalks, and over 2,000 lampposts, along with countless trees, shrubs, and flowering plants in "the Garden City of the West."Without losing sight of all the loss and suffering, it is important to remember how much of the city did not burn. Most heavy industries, including the stockyards, were located west or south of the burnt district, out of harm's way. The downtown railroad depots were leveled, but not the far more critical rail infrastructure. What the fire could not touch was Chicago's most important feature, its location, which made it more accessible than any place on earth to resources and markets throughout the globe at the very time when America was taking over world leadership in industrial enterprise.

Chicago quickly rebuilt and by 1875 little evidence of the disaster remained. The 100th anniversary of the fire was commemorated during the period October 3-10, 1971, with a series of events including a fire centennial dinner during which the Mayor expressed thanks to cities and countries that sent money after the fire. Other events included a fire prevention parade on State Street and an enormous lakefront fireworks display.

I heard an interesting "fact" in the summer which may or may not be true. Apparently the fire was so hot that people went into the lake to avoid the heat. They had to go deeper and deeper as the temperature of the fire grew to the temperature of bath water. Eventually when the fire went out, the heat had been so intense it had turned some of the sand to glass, which was broken up and kept as souvenirs by the folks in the lake. Apparently none of this glass has ever turned up in a museum and has been handed from generation to generation. The fact that nothing has ever come out in the public, probably invalidates this story, but it is fun nevertheless.

There is plenty more information available on the fire out here and here, but nothing on the special glass!

Comments